Doctoral students Ying “Nina” Hu (left), Matthew Hill (second from left) and Connor Parde work with Dr. Alice O’Toole, professor of cognition and neuroscience and the Aage and Margareta Møller Professor, in O’Toole’s Face Perception Research Lab. The four recently studied how people form first impressions from body shapes.

When you first meet someone, it’s likely that you judge their personality based on what little information you have.

While what we infer from faces has been well studied, new research from The University of Texas at Dallas suggests that people also form first impressions from body shapes.

Ying “Nina” Hu, a doctoral student in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, is the lead author of the study, recently published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. Hu works in the Face Perception Research Lab of Dr. Alice O’Toole, professor of cognition and neuroscience and the Aage and Margareta Møller Professor.

“A wide range of bodies and personality traits were included, so we’re not just saying that, for example, body weight predicts a perception of laziness. The effective body features go well beyond that, extending to more nuanced features, such as shoulder width.”

Ying “Nina” Hu, lead author of the study and a doctoral student in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences

“We found consistent, reliable trait inferences from body shapes,” Hu said. “A wide range of bodies and personality traits were included, so we’re not just saying that, for example, body weight predicts a perception of laziness. The effective body features go well beyond that, extending to more nuanced features, such as shoulder width.”

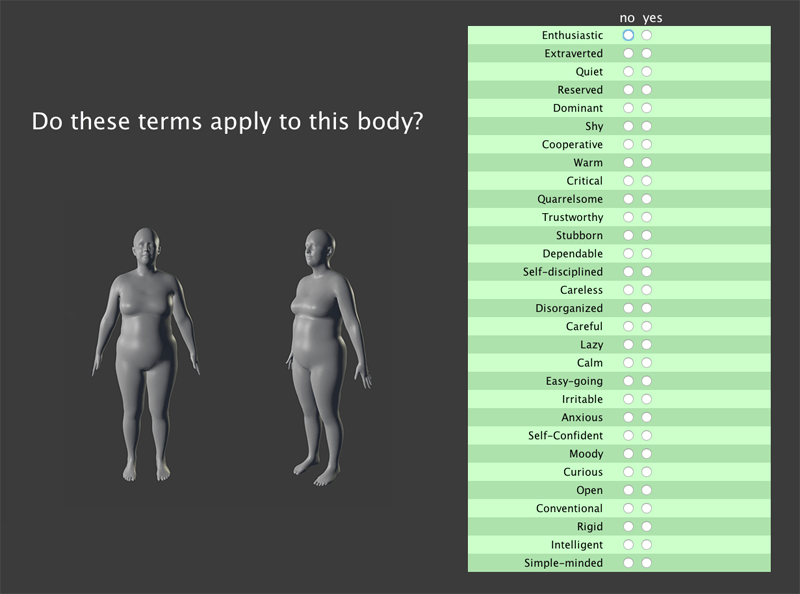

The study used 140 gray, 3D body models with the same face, split evenly between male and female. Doctoral student Matthew Hill explained that the body models were fashioned using a system created by the Max Planck Institutes in Tübingen, Germany.

“They’ve taken a large set of laser scans of real humans and built a model from the statistics they gathered,” he said. “They describe a body with a set of 10 dimensions. The 140 bodies we used were sampled randomly from a normal distribution of those 10 variables.”

Participants viewed the models from two angles and were given 30 adjectives — words such as “anxious,” “dominant” and “disorganized” — that they could assign to that body shape. Those word choices stemmed from the Big Five model, a taxonomy of personality traits dating to the 1980s that is often used in psychology research.

Hu said that the body models were presented in a standard arms-down, elbows-locked position because it was the closest thing to a neutral pose.

“Body language can, of course, change impressions,” Hu said. “People who feel powerful will spread out. If they feel powerless, they will wrap up. Even how you stand conveys part of your personality.”

Participants consistently linked pear-shaped female models and broad-shouldered male models — which both fit the classical gender stereotypes — with extraversion and irritability, traits classified as active personalities. More rectangular male and female models were presumed to be more passive, being described as trustworthy, shy and warm.

Study participants viewed the 3D body models from two angles and were given 30 adjectives that they could assign to that shape.

Connor Parde, another doctoral student in O’Toole’s lab, explained the group’s motivation for focusing on the body itself.

“Research has shown that people make important decisions based on trait inferences, like whom to vote for, whom to hire, criminal sentencing and so on,” Parde said. “Plenty of work has been done on first impressions from faces. But often, when seeing someone for the first time, you’re seeing much more.”

Hu suggested several potential paths forward for the findings before describing how they might be integrated with facial research.

“Personally, I think the most interesting follow-up is to incorporate first impressions from faces, and see how those interact with impressions from bodies,” she said. “If your face looks trustworthy, but your body doesn’t, what takes priority? Do we analyze the face and body separately, or are they integrated?”

O’Toole conceded that the inferences are expected to differ across ethnicity, geographic location and possibly the age group of the participants.

“We don’t expect these results mapping body shape and traits would apply in different cultures,” she said. “Nevertheless, we believe people tend to infer personality traits from body shape in systematic and reliable ways.”

While the study makes a statement about the reliability of these perceived links, the researchers asserted that any connection between body type and personality has not been substantiated. Nevertheless, these presumptions still exist.

“There’s no strong evidence linking body type to personality traits,” O’Toole said. “We weren’t looking at that directly here in any way. We’re talking about perceptions.”

With that in mind, the researchers recommended being mindful of our own judgment habits.

“Stereotypes based on body shape can contribute to how we judge and interact with new acquaintances and strangers,” Hu said. “Understanding these biases is important for considering how we form first impressions.”